By Kai-lung Hui, Allen Huang, Hyungsoo Lim, and Hyson Lam

Posted on: 2022-03-23

Evidence from the Hong Kong Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement during 2019-2020[i]

Introduction

The influence of media on social movements has been extensively researched by scholars in a wide range of fields, including Political Science, Sociology, Communications, and Information Systems. This may be due to the sizable societal impact social movements could bring and the growing use of information technology to power social movements.

Research generally suggests that mass media has a significant impact on political behaviors. In particular, traditional media such as television and radio broadcasts affect political behaviors through direct and indirect persuasion, whereas social media influence occurs primarily through social networks[ii] and the construction of collective identities[iii]In our project, print media and social media data and arrest records during the Hong Kong Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement (Anti-ELAB Movement) are used to examine whether media discussion is causally linked to political violence.

The Hong Kong Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement

Hong Kong has experienced unprecedented turmoil in 2019 and early 2020, with a multitude of protests and violent incidents associated with the Anti-ELAB movement. The movement was sparked by the Extradition Law Amendment proposal triggered by the Tony Chan Tong Kai incident.[iv] It evolved into a social movement against the Chinese and HKSAR government, accumulated by the deep-seated Hong Kong-mainland China conflicts and the Umbrella Movement in 2014.

The Anti-ELAB movement fueled protesters’ hatred of the authorities. Additionally, it triggered conflicts among people and organizations with different ideologies. The polarization of sentiment and ideology was manifested towards companies. Discrimination and attacks were often seen when a company or an organization expressed concern about the movement or violence; or was perceived to be affiliated with a certain political ideology or a certain capital.[v]

Instead of relying on political entities to organize the movement, the Anti-ELAB movement embraced a novel “No Center Stage (無大台)” concept. Most protesters promoted a non-hierarchical culture, where they did not have a formal leader to lead the movement.[vi]

Social media became an essential platform for protesters to coordinate the movement. For example, they used LIHKG and Telegram to share protest information, coordinate activities, and appeal to other citizens. These open social media networks provided protesters with the flexibility to discuss movements’ strategies and convene protests of varying scales. This might be one of the reasons for the upsurge in radical behaviors such as riot and vandalism, since political emotions can be easily manipulated over the Internet.

Our Research

Our research investigates how various media channels affect the protests and political violence during the Anti-ELAB movement. We conjecture that both print media and social media play a role in facilitating the movement, where protestors and selected press and media make use of those channels to coordinate movement activities and spread their political ideologies to the general public.

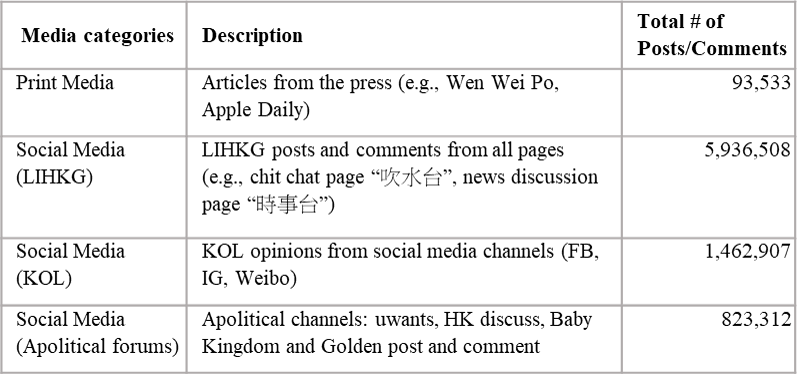

Our sample period covers June 2019 to February 2020. We obtained over 8 million print media articles and social media posts and comments from Wisers Information Limited, one of the industry-leading experts in media big data intelligence (see details of the media data in Table 1 below).

Table 1. Print media and social media sample description

Impact of Media Mention on Arrest Locations

To measure participation and violent activities during the Anti-ELAB movement, we use the arrested person records under the “Operation Tiderider.”[vii] The arrested persons data set comprises 8,049 arrest records by 5,438 unique persons and 2,471 damage act records with 278 unique victim companies and organizations.We extracted the entities mentioned in the media using a natural language processing algorithm called named-entity recognition (NER), which classifies the entities by categories such as location, brand, and company names.

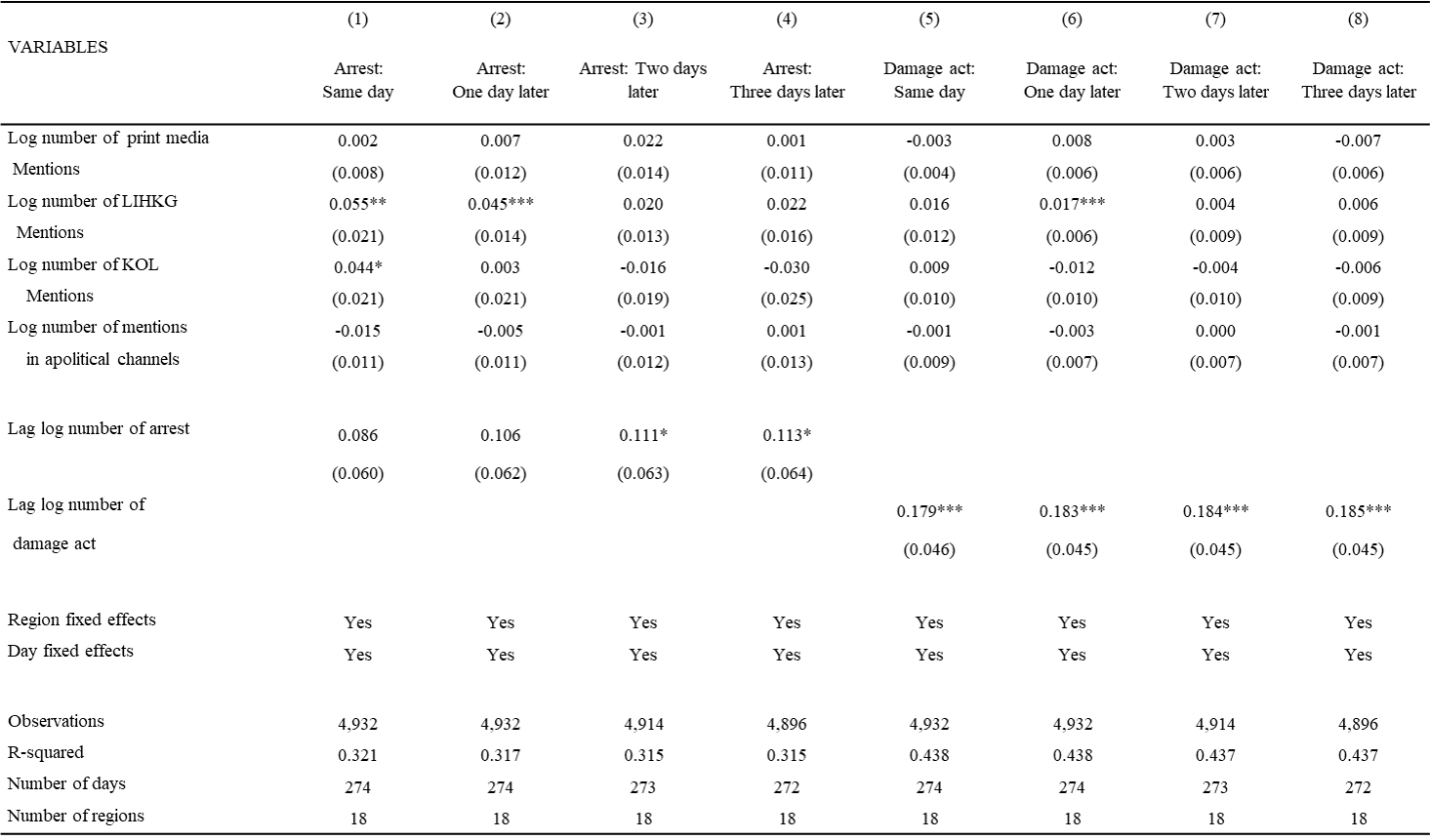

We first analyze how media mentions of a location affect the arrests and damage acts in that location. We use the location keywords extracted by NER and manually map the top 2,000 most frequently mentioned locations in each media channel into one of the 18 districts in Hong Kong[viii]. We also aggregate media mentions and arrested person records by day. Using the panel data of media mention and arrested persons by date and location, we conduct a series of panel regression models to estimate how media mention of a location affects the arrests and vandalisms in the same district on the same day and one, two, and three days later.

We use various methods to establish that the media mention affects . First, we use lead-lag relation between media and arrested persons by defining the date of media mention based on posts during the 24 hour period before 12pm because most incidents occur after 12pm. Second, we control for the number of arrests and damage acts during the previous day in the regressions.

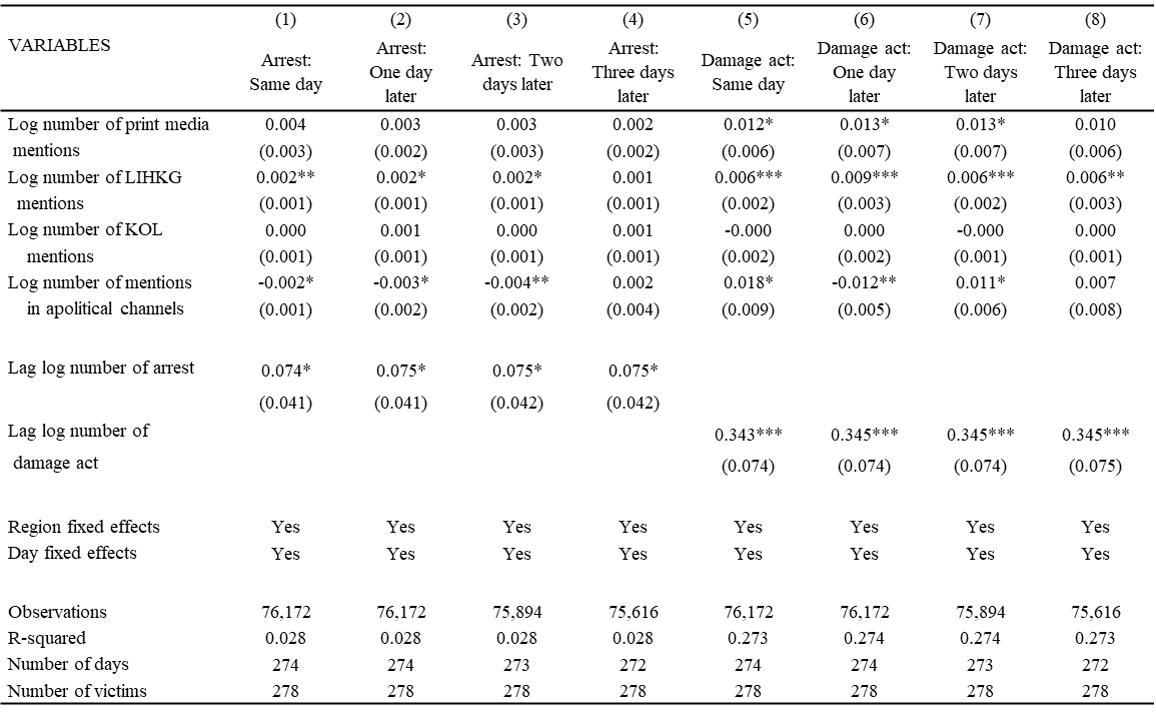

The results show that the locations mentioned on LIHKG have a significant effect on arrests and vandalism. 1% increase in LIHKG mentions on location is associated with a 5.5% increase of arrests within the same day and a 4.5% increase on the next day. KOL mentions have a significant impact on the arrests within the same day with a 4.4% increase. In terms of vandalism, a 1% increase in LIHKG mentions is associated with a 1.7% increase of vandalism on the next day.

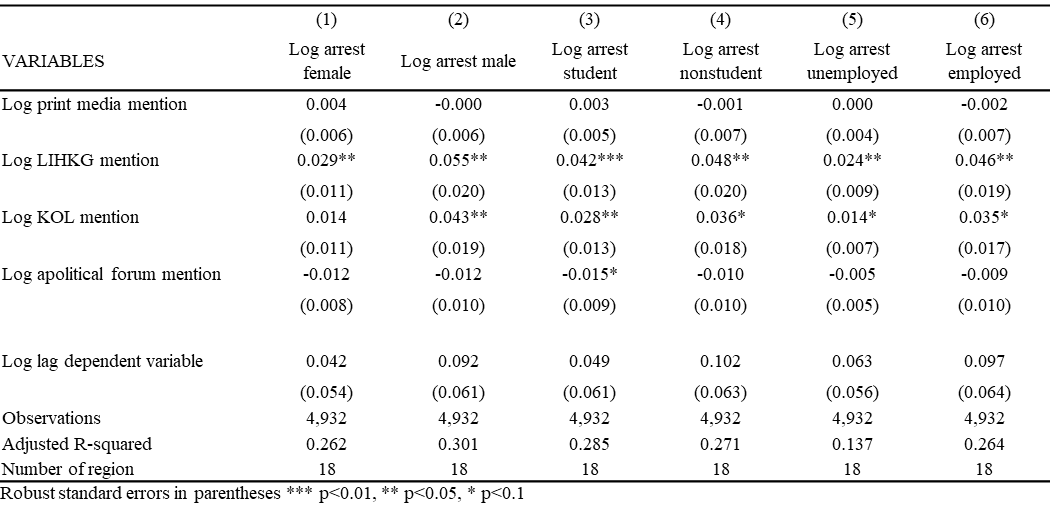

Additional analyses show that the effect of LIHKG mentions on arrests varies with demographics, including gender and student status. Consistent with prior literature[ix], the impact on males is much larger than females. 1% increase in LIHKG mentions on location are associated with 5.5% and 2.9% increases on male and female arrests respectively. Similarly, KOL mentions appearing to affect only male but not female arrests.The results show that the locations mentioned on LIHKG have a significant effect on arrests and vandalism. 1% increase in LIHKG mentions on location is associated with a 5.5% increase of arrests within the same day and a 4.5% increase on the next day. KOL mentions have a significant impact on the arrests within the same day with a 4.4% increase. In terms of vandalism, a 1% increase in LIHKG mentions is associated with a 1.7% increase of vandalism on the next day.

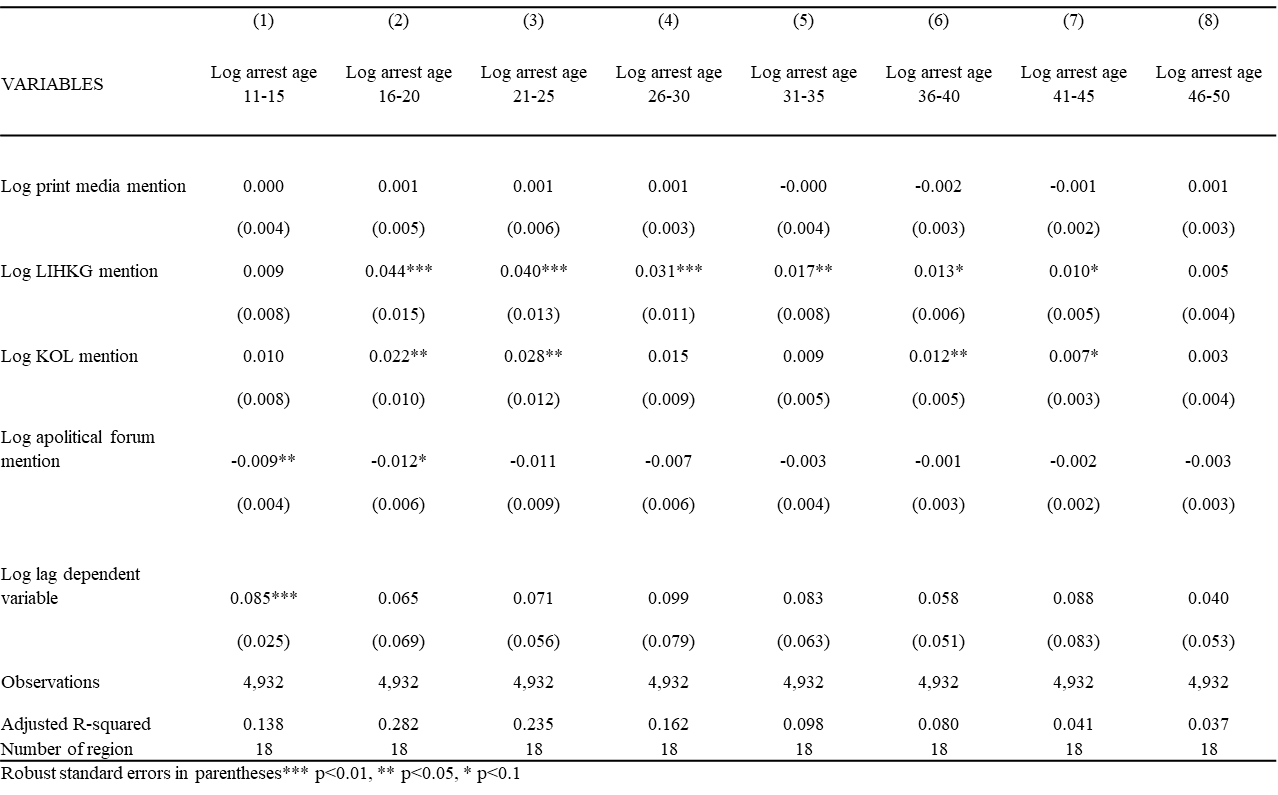

LIHKG mentions have a strong and statistically significant impact on arrest among most age groups, especially between the age of 16-30, where a 1% increase on location mentions leads to at least 3% increase in arrests. This effect decreases with age, which is consistent with younger generations being the primary users of social media. Similarly, KOL mentions have a significant impact on arrest age between 16-25, with the effect size around 2-3%.

Impact of Media Mention on Victim Companies

We apply a similar regression strategy on media mention of victim companies or organizations. We manually labelled the top 2,000 keywords of each media category as one of the 278 victim companies or organizations identified from our arrested person records. We tabulate the results as follows:

The results show a significant impact of LIHKG victim mentions on arrested persons, with the effect size of 0.2% and 0.6% on arrests and damage acts on the same day respectively. Such impact persists a longer time period, where the impact of LIHKG mentions remains statistically significant after 2-3 days.

Conclusions

Our study shows a strong evidence that social media, especially LIHKG, has a significant impact on people’s violent political behavior during the Anti-ELAB movement. Our results also suggest that this influence is particularly apparent in the younger generation. We plan to conduct further empirical tests by using natural language processing algorithms to extract additional information from media texts, including sentence structure and message sentiment. Analyzing these features can provide insights on which type of content contributed the most to social movement and violent activities. This research contributes to academic research by documenting evidence consistent with the media’s casual influence on people’s behavior. We also contribute to government policy-making by providing insights into what contributed to mass social movements. As citizens, we should be aware of how the media can influence our behavior, and act rationally and proportionately when taking part in political campaigns and activities.

________________________________________

[i] Photo retrieved from https://unsplash.com/photos/qeYJ1RSRV-U.

[ii] See Enikolopov & Patrova (2017). Mass media and its influence on behavior. Els Opuscles del CRUIE num, 44.

[iii] See Gerbaudo, P., & Treré, E. (2015). In search of the ‘we’ of social media activism: introduction to the special issue on social media and protest identities. Information, communication & society, 18(8), 865-871.

[iv] More information is available at https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3005942/hong-kong-man-wanted-taiwan-murder-case-could-escape.

[v] Photo retrieved from https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3036260/daughter-maxims-founder-hits-out-again-hong-kong-protesters.

[vi] See Ku (2020). New forms of youth activism–Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Bill movement in the local-national-global nexus. Space and Polity, 24(1), 111-117.

[vii] The “Operation Tiderider” is the operation launched by the Hong Kong Police Force in response to large-scale protests and public order disturbances beginning in June 2019.

[viii] The 18 districts include Islands, Kwai Tsing, North, Sai Kung, Sha Tin, Tai Po, Tsuen Wan, Tuen Mun, Yuen Long, Kowloon City, Kwun Tong, Sham Shui Po, Wong Tai Sin, Yau Tsim Mong, Central and Western, Eastern, Southern and Wan Chai. More details of the classification is available here. https://www.rvd.gov.hk/doc/tc/hkpr13/06.pdf.

[ix] See Bardall, Bjarnegård, & Piscopo (2020). How is political violence gendered? Disentangling motives, forms, and impacts. Political Studies, 68(4), 916-935.

Prof. Yang highlights enterprise AI breakthrough at HKUST Unicorn Day, showcasing LayerZero AI's custom embedding technology.

Prof. Yi Yang, Director of the Center, joins industry leaders in a panel discussion on cutting-edge GenAI risk management strategies during the launch of the second cohort of the Generative AI (GenAI) Sandbox initiative held on 28 Apr 2025.

At the closing Pitch Fest of the first-ever Web3 Ideathon, top tertiary student teams showcased their groundbreaking Web3 concepts to industry experts.