By Kai-lung Hui, Allen Huang, and Raman Kaur

Posted on: 2022-04-27

Introduction

Barely awake from the previous night’s sleep, the student changes into a better-looking T-shirt. With a bowl of cereals in her hands, she walks over to her study table and switches on her laptop to access the software that has captured the zeitgeist of a new era – Zoom. The face of her favorite teacher gleams with enthusiasm through the tiny screen as the two-hour “hands-on” biochemistry lab experiment lecture begins.

Globally, such a routine became a reality for students when the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the normal operations of schools. Though distance learning courses have existed for some time, it is only in the last two years that there has been a significant large-scale shift to distance learning. To balance the learning needs of students and staff safety, many schools halted in-person teaching and oscillated between Purely Online, Hybrid Mode, and even Blended Learning teaching modes. Such a drastic shift towards these delivery modes inevitably raises several questions about online learning, including whether and how students’ satisfaction with learning has been affected. The availability of distinct online learning modes may also engender curiosity about whether certain online learning modes work better than others.

Current Research

Numerous research studies have already been conducted in this field, and the results are mixed, suggesting that the rapid proliferation of online teaching modes can be a double-edged sword. While more flexibility and convenience in learning are commonly cited as the biggest benefit of online distance learning, several studies have also pointed out that students need more discipline to succeed in online courses when compared to face-to-face ones. Online courses require more personal responsibility and motivation, not to mention greater time management skills. Moreover, online studies, especially Purely Online, may substantially reduce student-to-student and student-to-teacher interaction, which could have an inimical effect on students’ learning outcomes and satisfaction, especially in courses where interaction and discussions are important for learning.

Various research studies have compared students’ test results in face-to-face classes to those in online classes (Alpert et al., 2016; Bettinger et al., 2017; Brown & Liedholm, 2002; Xu & Jaggars, 2016; Swoboda & Feiler, 2016). Many of these studies find that students perform worse in Purely Online and Hybrid Mode when compared to face-to-face classes. Comparing Blended Learning and face-to-face mode, Alpert et al. (2016) observed no statistically significant difference in student outcomes.

Our Research and Methodology

The aim of our research study is to learn how students’ perception of instructors and courses change after the introduction of online teaching modes by measuring the changes in student satisfaction levels towards courses and instructors. Although several studies looking into the effectiveness of online teaching have already been conducted, most of them have only been able to focus on a limited number of courses. This could give a rather pedantic view of the issue. These studies also face limitations in controlling for course difficulty levels due to data scarcity. Further, most studies consider only one type of online learning mode (most commonly Purely Online) and hence cannot compare across different distance learning modes.

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) collects student opinions on courses and instructors at the end of each semester. With the wealth of panel data that spans across faculties and instructors, our data allows us to cover undergraduate and postgraduate studies in various disciplines, including science, humanities, business, engineering, and interdisciplinary programs. There are several different modes of online learning and our data allows us to cover all the three main ones, including Purely Online, Hybrid Mode, and Blended Learning. In Purely Online mode students participate in classes via synchronous or asynchronous virtual sessions. In Hybrid mode, some students participate in classes in-person while others participate virtually. Blended Learning mode is where instructors combine in-person instruction with online learning activities, with students completing some components of courses online and the rest in face-to-face classes[i].

Our data covers 2,103 courses and 1,085 instructors. We use data starting from Fall 2017, during which the majority of the courses were face-to-face, up until Fall 2020. There was a major shift to online courses in the Fall 2019 semester when Hong Kong experienced widespread protests (this represents an exogenous shock in our study). Prior to Fall 2019, only a handful of courses were taught online and at the discretion of instructors’ choices. A mere 32 courses were taught via Blended Learning Mode between Fall 2017 to Spring 2018 semester and no courses were taught in Hybrid or Purely Online Mode during this period.

Model Specification

The following is our main model specification:

We have two main dependent variables (y_it), Instructor Score and Course Score, for both of which the maximum score is 100 and the minimum is 0. Our main independent variables include the dummy variables of Blended Learning, Hybrid Mode, Purely Online Mode, and Fall 2019. Along with these main effects, we have included Class Size (Logged), Course Level, Mainland Origin, and Female as control variables.

Further, to control for the course characteristics, we added course-specific assessment percentages, including Lab Percentage, Participation Percentage, Exam Percentage, and Project Percentage. The sum of these percentages and assignment percentage is 100 for all courses in our regression and we adopt the same model as equation (1).

Additionally, to observe how these assessment percentages moderate the main effects in equation (1), we interact the assessment percentages and Class Size (logged), Course Level, and Mainland Origin with the main independent variables.

Empirical Analysis & Preliminary Results

Effect of Online Learning Modes on Student Satisfaction

Our preliminary results suggest that students across faculties and course levels at HKUST mostly welcome Hybrid Mode. This conclusion is indicated by the consistent significant and positive effects on Instructor and Course Scores in the regression results.

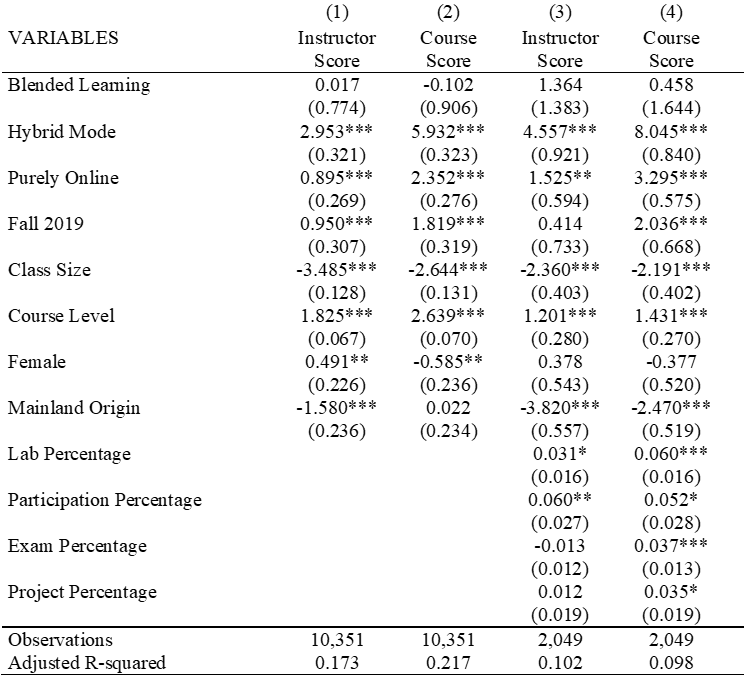

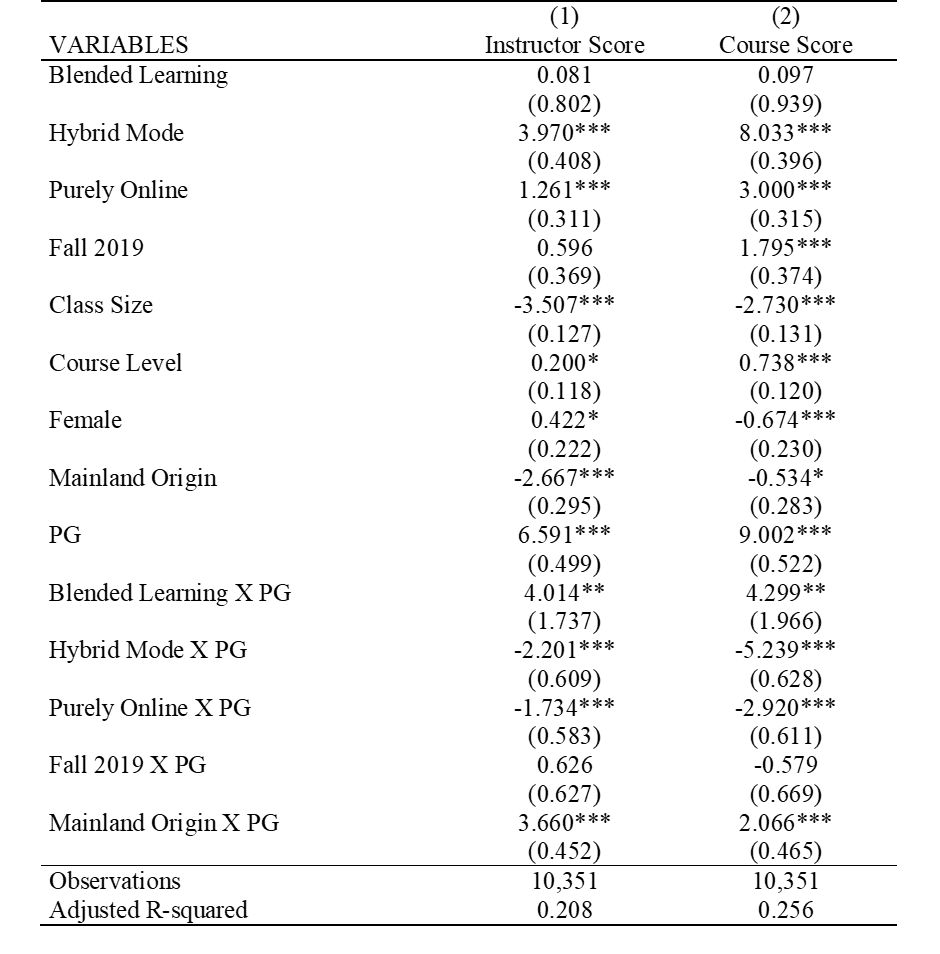

Regressions in Tables 1 below show that the Hybrid mode has the largest significantly positive effect on both Instructor and Course Scores when compared to other teaching modes (coefficient = 2.952 (column 1), p <0.01 and coefficient = 5.932 (column 2), p<0.01 in table 1). Put differently, a course taught in hybrid mode increases instructor evaluation by almost 3 score points and course evaluation by almost 6 points.

Table 1. Baseline Estimation Results and Estimation Results with Course Characteristics

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses, *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

As UG and PG students may respond differently to various means of instructions, we run the regression on the pooled sample with interaction with PG dummy variable as shown below. Although the positive effect of Hybrid Mode on the Instructor and Course Scores reduces when we interact the variable with PG (coefficient = -2.201 (column 1), p<0.01 and coefficient= -5.239 (column 2), p<0.01 in table 2), Hybrid Mode still has a significantly positive effect on Instructor and Course Scores for PG students.

Table 2. Heterogeneity across Student Groups

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses, *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

The positive effect of the Hybrid Mode on student satisfaction could be owing to the learning flexibility offered by this teaching mode. As students get to choose whether to attend courses in-person or online each week, they have more control over their schedules and can better allocate time and effort between courses and other commitments. Students can also save transportation time when they like.

We also find that Purely Online mode is welcomed by students, mostly at the undergraduate level (coefficient = 2.352 (column 2), p<0.01 and coefficient = 3.295 (column 4), p<0.01 in table 1). As observed in table 2, PG students appreciate Purely Online mode much less than UG students. The first reason for this could be that UG students value and prioritize flexibility and convenience more than PG students who, unlike the former, tend to get less involved in extra-curricular activities and are more focused on their studies during the period of their programs.

The second explanation is that junior-level courses which tend to teach fundamental contents may be easier to learn in Purely Online mode as opposed to senior-level courses which are more complex and often require more interaction. This reasoning is consistent with our finding that PG students enjoy Blended Learning courses more than UG students (coefficient = 4.014 (column 1), p<0.01 and coefficient = 4.299 (column 2), p<0.01 in table 2).

The above results contrast many of those in hitherto studies in which Purely Online and Hybrid Modes have shown to have a detrimental effect on both student satisfaction and performance (Brown & Liedholm, 2002; Alpert et al., 2016; Xu & Jaggars, 2016; Bettinger et al., 2017; Young & Bruce, 2020; Tratnik et al., 2019). The contrasting results could be due to the dissimilarities in the empirical settings of our research studies. Whilst much of the previous research is based on data from Western (and mainly the United States) higher education institutions, our study is based on data from an East Asian school. The general cultural and attitudinal differences in learning between students of the two regions could have an impact on the receptiveness towards online learning and the accompanying effects. For instance, Asian students may be less sensitive to the decline in student-to-student or student-to-teacher interaction as compared to students in Western universities where “many students enjoy face-to-face interaction with their professors, at least at places where such interaction is common and expected” (McPherson & Bacow, 2015).

Further Exploration and the Effect of Additional Variables on Student Satisfaction

Other than the effect of different learning modes on student satisfaction, we observed several interesting effects of additional variables. The interaction between these additional controls and our main variables also provides more insight into the main drivers of the main effects discussed above.

Firstly, Class Size significantly reduces Instructor and Course Score in our regressions (coefficient = -3.485 (column 1), p<0.01 and coefficient = -2.644 (column 2), p<0.01 in table 1). This result is unsurprising and has been documented in various studies prior (Johnson, 2010; Bandiera et al., 2010; De Giorgi et al., 2012) as large class size maybe lead to lowered student-teacher interaction, lessened specialized attention for students as well as a more disruptive environment.

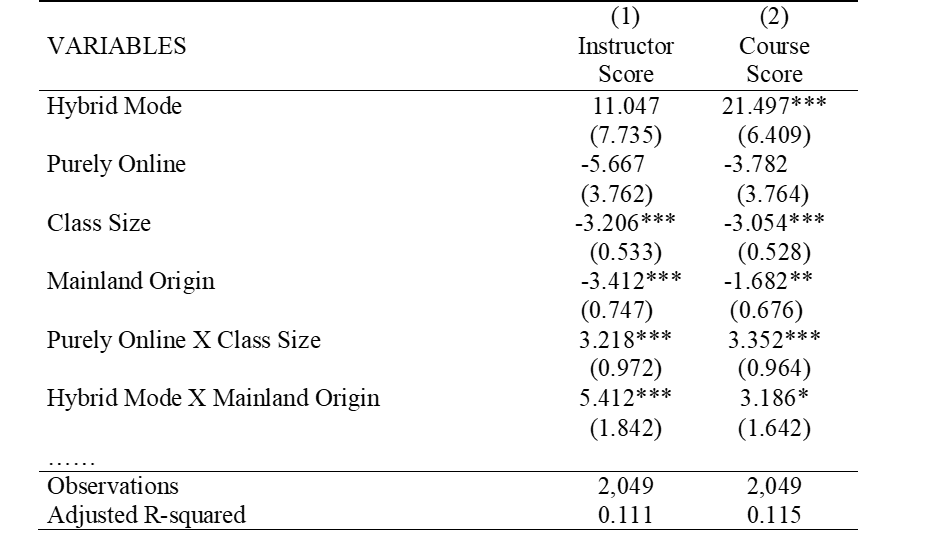

What is interesting in our study is that the interaction effect between Purely Online and Class Size is significantly positive and larger than the significant negative effect of Class Size in absolute terms (coefficient = 3.218 (column 1), p<0.01 and coefficient = 3.352 (column2), p<0.01 in table 3) implying that Purely Online mode can be used to regulate the negative impact of large Class Sizes. Further exploration also suggests that the significantly positive effect of Purely Online mode reported in our baseline regressions is mainly driven by the student ratings from large class size courses.

The main takeaway from these results is that Purely Online mode may be more suitable for bigger classes than those with small class sizes as the former are typically designed to be less interactive anyways, for example, Econ 101s.

Table 3. Heterogeneity in the Main Effect across Course Characteristics

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses, *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

Secondly, our results suggest that when an instructor is from the Mainland, student satisfaction, at the undergraduate level, significantly declines (coefficient = -2.667 (column 1), p<0.01 and coefficient = -0.534 (column 2), p<0.01 in table 2). When we limit our sample to PG, the effect of Mainland is significant and positive. This difference could be driven by the fact that the majority of the students at the postgraduate level are from the Mainland and may thus have better rapport and perspective toward Mainland instructors than undergraduate students who may be influenced by ongoing political and social issues. Interestingly, the interaction effect between Hybrid Mode and Mainland Origin is significantly positive and is larger than the negative main effect of Mainland Origin in absolute terms as reflected in table 3. As the majority of the sample in table 3 is UG, this implies that when an instructor is from the Mainland, UG students’ satisfaction with instructor teaching may improve with Hybrid Mode.

Thirdly, we find that as course levels increase, students’ satisfaction with instructors and courses improves as well (e.g., coefficient= 1.825 (column 1), p<0.01 and coefficient= 2.639 (column 2), p<0.01 in table 1). This may be because students tend to take more specialized courses of their own choice in senior years (specialized courses tend to be of a higher level).

Conclusion

Our preliminary findings indicate that students at HKUST prefer online learning modes, particularly Hybrid Mode and Purely Online modes. Further research suggests that these learning modes are particularly popular among undergraduate students and in classes with large class sizes. Apart from that, we find that as course levels increase, students' satisfaction with learning tends to improve. As this is an ongoing project, we intend to expand our research by collecting additional data and conducting additional tests to determine the study's robustness and implications.

References:

Alpert, William T., Kenneth A. Couch, and Oskar R. Harmon. 2016. "A Randomized Assessment of Online Learning." American Economic Review, 106 (5): 378-82.

Bandiera, O., Larcinese, V., and Rasul, I. 2010. "Heterogeneous class size effects: New evidence from a panel of university students." The Economic Journal, 120 (549): 1365-1398.

Bettinger, E., Doss, C., Loeb, S., Rogers, A., & Taylor, E. 2017. "The Effects of Class Size in Online College Courses: Experimental Evidence. " Economics of Education Review, 58: 68-85.

Bettinger, Eric P., Lindsay Fox, Susanna Loeb, and Eric S. Taylor. 2017. "Virtual Classrooms: How Online College Courses Affect Student Success. " American Economic Review, 107 (9): 2855-75.

Brown, Byron, W., and Carl E. Liedholm. 2002. "Can Web Courses Replace the Classroom in Principles of Microeconomics?" American Economic Review, 92 (2): 444-448.

De Giorgi, G., Pellizzari, M., and Woolston, W. G. 2012. "Class size and class heterogeneity." Journal of the European Economic Association, 10 (4): 795-830.

McPherson, Michael S., and Lawrence S. Bacow. 2015. "Online Higher Education: Beyond the Hype Cycle." Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29 (4): 135-54.

Johnson, I.Y. 2010. "Class size and student performance at a public research university: A crossclassified model." Research in Higher Education, 51 (8): 701-723

Swoboda, Aaron, and Lauren Feiler. 2016. "Measuring the Effect of Blended Learning: Evidence from a Selective Liberal Arts College." American Economic Review, 106 (5): 368-72.

Tratnik, A., Urh, M. and Jereb E. 2019. "Student satisfaction with an online and a face-to-face Business English course in a higher education context." Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 56 (1): 36-45.

Xu, Di, and Shanna, Jaggars, S. 2014. "Performance Gaps between Online and Face-to-Face Courses: Differences across Types of Students and Academic Subject Areas. " The Journal of Higher Education, 85 (5): 633-659.

Young, S. and Bruce, M. A. 2020. "Student and Faculty Satisfaction: Can Distance Course Delivery Measure Up to Face-to-Face Courses?" Educational Research: Theory and Practice, 31 (3): 36-48.

[i] More information is available at https://www.leadinglearning.com/hybrid-vs-blended-learning/

Prof. Yang highlights enterprise AI breakthrough at HKUST Unicorn Day, showcasing LayerZero AI's custom embedding technology.

Prof. Yi Yang, Director of the Center, joins industry leaders in a panel discussion on cutting-edge GenAI risk management strategies during the launch of the second cohort of the Generative AI (GenAI) Sandbox initiative held on 28 Apr 2025.

At the closing Pitch Fest of the first-ever Web3 Ideathon, top tertiary student teams showcased their groundbreaking Web3 concepts to industry experts.